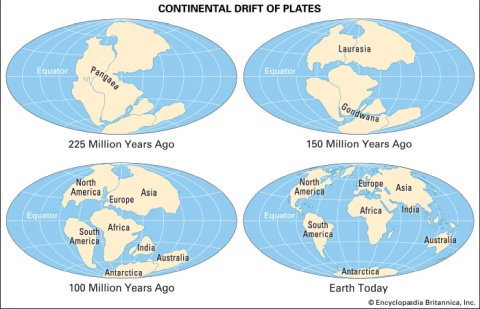

A Shifting Puzzle: The Idea of Continental Drift

Long before plate tectonics was fully understood, scientists observed a peculiar pattern: the

continents seemed to fit together like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle. The most striking example is

the eastern coast of South America and the western coast of Africa. In the early 20th century,

German meteorologist and geophysicist Alfred Wegener championed the idea of continental

drift, proposing that the continents were once joined in a single supercontinent he named

Pangaea, which later broke apart and drifted to their current positions.

Wegener supported his hypothesis with compelling evidence: matching fossil records across oceans,

similar rock formations and mountain ranges found on widely separated continents, and evidence of

ancient climates (like glacial deposits in tropical regions). However, he lacked a plausible

mechanism to explain how continents could move, leading to widespread skepticism from the

scientific community at the time.

Unveiling the Mechanism: Plate Tectonics

It took several decades and advancements in oceanography, seismology, and paleomagnetism to uncover

the driving force behind continental drift. By the 1960s, a new, more comprehensive theory emerged:

plate tectonics. This theory posits that the Earth's rigid outer layer, the lithosphere,

is broken into several large and small pieces called tectonic plates. These plates

are not stationary; they are in continuous, slow motion, floating atop the semi-fluid layer known as

the asthenosphere in the Earth's upper mantle.

The primary driver for plate movement is convection currents within the Earth's mantle. Heat

from the Earth's core causes molten rock to rise, cool, and then sink, creating a slow but powerful

circulating motion that drags the overlying plates along. This continuous motion leads to three main

types of plate boundaries:

- Divergent Boundaries: Where plates move apart, such as at mid-ocean ridges,

creating new oceanic crust through volcanic activity. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a prime example.

- Convergent Boundaries: Where plates collide. This can result in one plate

subducting (sliding) beneath another, forming deep ocean trenches, volcanic arcs, and powerful

earthquakes (e.g., the Pacific Ring of Fire). If two continental plates collide, neither can

easily subduct, leading to the formation of massive mountain ranges like the Himalayas.

- Transform Boundaries: Where plates slide horizontally past each other,

generating significant friction and often causing earthquakes, such as along the San Andreas

Fault in California.

Earth's Composition: Layers of a Dynamic Planet

Our understanding of plate tectonics is deeply intertwined with the Earth's internal structure.

Through seismic studies (analyzing how earthquake waves travel through the Earth), we've pieced

together a layered model of our planet:

- Crust: The outermost, thinnest layer, varying in thickness from about 5 km

(oceanic crust) to 70 km (continental crust). It's composed primarily of silicates.

- Mantle: A thick layer of dense, hot, semi-solid rock extending to about 2,900

km deep. The upper part of the mantle includes the asthenosphere, which allows the lithospheric

plates to move.

- Outer Core: A liquid layer composed mainly of iron and nickel, extending to

about 5,150 km deep. Convection currents within the outer core are responsible for generating

Earth's magnetic field.

- Inner Core: A solid ball of iron and nickel at the very center of the Earth,

extremely hot and under immense pressure.

The heat generated from radioactive decay within the Earth's core and mantle is the engine that

drives these internal processes, including mantle convection and, consequently, plate tectonics.

The Evolution of Earth and Life

Plate tectonics is not merely a geological phenomenon; it is a fundamental force that has shaped the

evolution of our planet and life on it. Over billions of years, the slow dance of continents

has:

- Influenced Climate: The arrangement of continents affects ocean currents and

atmospheric circulation patterns, profoundly influencing global and regional climates over

geological timescales.

- Created Habitats: The formation of mountain ranges, ocean basins, and volcanic

islands provides diverse environments for life to evolve and adapt.

- Driven Speciation: The separation and reconnection of continents have isolated

populations, leading to the development of new species and the unique biodiversity we see today.

- Recycled Elements: Plate tectonics plays a crucial role in the Earth's

biogeochemical cycles, bringing new rock to the surface through volcanism and returning material

to the mantle through subduction, thereby regulating the planet's atmospheric composition and

nutrient availability.

From the birth of supercontinents like Rodinia and Pangaea to their eventual fragmentation, the

Earth's surface has been in a continuous state of transformation. This dynamic process continues

today, reminding us that our planet is a living, breathing entity, constantly reshaping itself in a

slow but powerful geological ballet.